Johann Wilhelm Ludwig Gleim (1719-1803) was one of the most widely read poets of his time and a close friend of many other poets and thinkers. Friendship was a cult in the 18th century, and Gleim was perhaps the most passionate representative of this cult. As a poet, as a genius of friendship, as a literary activist and promoter, he was a central figure in the literary communication of the Enlightenment.

Gleim's first work was already a sensational success: humorous poems of wine and love (1744) modelled on the Greek poet Anacreon. His poems on Frederick II of Prussia and his campaigns in the Seven Years' War were even more successful. Gleim was also widely known as a writer of fables. With these and other poems, he set impulses for literary development. He was one of the most prominent writers of letters of his time.

Gleim began to gather his friends around him in portraits at an early age. Over the years, the walls filled up. At the same time, his library grew. His correspondence with over 500 people took on the characteristics of a manuscript archive. Gleim systematically expanded these collections in order to document the literary development and the culture of friendship of his time, and provided for their preservation in his will.

After his literary successes, Gleim was known as the 'German Anacreon', the 'Prussian Grenadier' or the 'Hüttner'. The active support of many younger poets earned him the nickname "Father Gleim". He remained an authority in the literary world into old age, even though a new generation had long since set the tone.

learn more

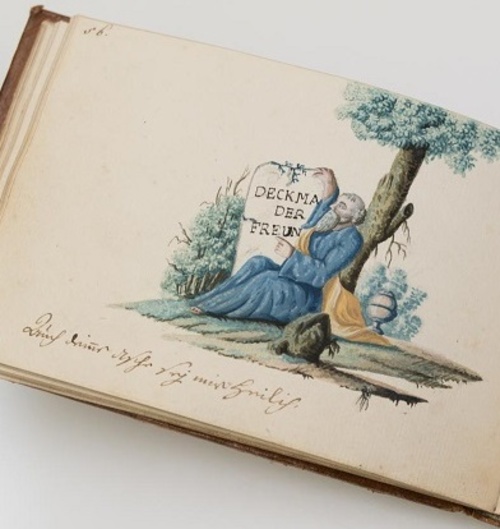

The 18th century, the Age of Enlightenment, is also known as the "Century of Friendship". Gleim himself was a genius of friendship. Friendship in this period was linked to new values and emotionality.

Gleim and his contemporaries followed the model of virtuous friendship, which was represented in antiquity by Aristotle. Those who represented the (new) values of the Enlightenment called each other friend. Friendship was not only practised in personal encounters, but also in letters. As more and more people became literate, a new written culture of friendship developed. To this day, friendship is important for people and also for society. How has the culture of friendship changed over the centuries? How do we experience friendship in our own lives? How do social connections change as a result of new media? What is the relationship between love and friendship? As a museum of friendship, the Gleimhaus invites visitors to explore questions about friendship in the past and present.

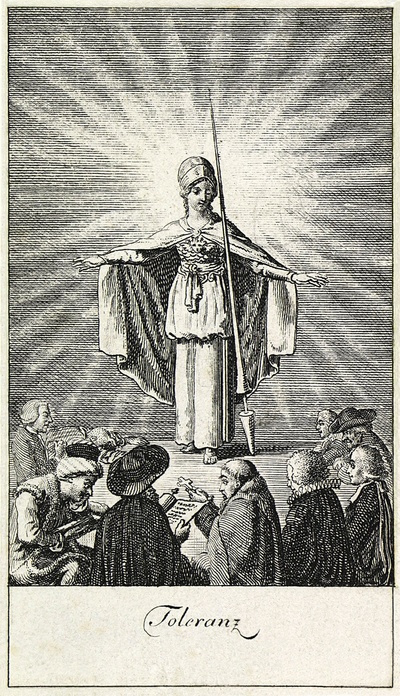

Tolerance (or forbearance) was one of the great ideals of the Enlightenment. This emerged naturally from two central concepts of the era: namely, that all human beings are inherently endowed with dignity and fundamental rights and, furthermore, that the various religions and denominations have a common core.

Religions have a lot in common with each other - an idea that was not easily expressed openly. The philosopher Christian Wolff was expelled from his chair at the University of Halle in 1723 because he had declared that the Chinese could also be virtuous. According to Christian understanding, only Christians could know what God wanted. And even towards the end of the century, Lessing felt compelled not to present these thoughts openly, but to dress them up in a stage play: "Nathan der Weise" (Nathan the Wise).

In Enlightenment states, religious freedom was a state principle. The Prussian King Frederick II, for example, declared that everyone should "nach seiner Façon selig werden " (be blessed according to his façon). From a political point of view, this was pragmatic, as the integration of well-educated people of other religions or other origins increased prosperity.

In the 18th century, tolerance was mostly related to religion, but also to culture and anthropology. Herder, for example, believed that geography and experience led to great diversity among people and cultures, but not to different values. From the diversity of religions, cultures and ethnicities, the focus shifted to the commonality, the universal humanity.

The Enlightenment did not begin with a single date and, above all, it is not complete. But it characterised a century in a very special way: the 18th century is regarded as the Age of Enlightenment. The intellectual movement swept across the whole of Europe. In the name of reason, a battle was waged against prejudice and superstition.

The sciences made significant efforts to explore the world and the laws of nature. People had become sceptical about the religion of revelation and the belief in miracles. They were replaced by the idea of a 'natural' religion based on reason.

It was no longer original sin that determined the image of humanity, but its reason, sense of community and sense of justice. Instead of waiting for redemption in the afterlife, people now sought happiness and fulfilment in earthly life. What was new was the idea that all people were inherently endowed with fundamental rights. This led to a new definition: the common good as a state objective.

Throughout the era, there was a certainty that reason and education would bring progress. Education as a person and as a citizen played an important role in this. In this vision of an ethical future, the individual could in turn contribute to the common good.

Enlightenment is a movement - to this day.

Humanity, humaneness, human rights, human duties, human dignity, and human love – all of these are encompassed by the concept of "humanity." Through the writings of Johann Gottfried Herder, it became a central tenet of the Enlightenment.

Reason and goodness characterise human beings. However, according to Herder, they are only inherent in humans in potential form. It is only through the development of these dispositions that humans achieve humanity. The very fact that this is possible is, in turn, a unique characteristic of humans, as only they possess reason and language, and thus the ability to perfect themselves.

Education therefore plays a central role. Education is understood not only as the acquisition of knowledge and skills but also as the development of personality – the shaping of the individual into a fully realised human being. Its goals are freedom of action within one's own life and effectiveness for society.

Connected to this was the belief that education would lead to the perfection of both the individual and society, creating the foundation for continuous progress.